Explorer Ernest Shackleton May Have Known His Ship ‘Endurance’ Wasn’t Equipped to Survive the Antarctic Ice

The vessel, which sank in November 1915, had structural shortcomings, including weak deck frames and no diagonal beams to strengthen the hull, a new study argues

Three weeks after explorer Ernest Shackleton ordered his men to abandon their ship, Endurance, in the fall of 1915, the vessel sank off the coast of Antarctica. Its fate has long been attributed to a weak rudder torn off by a sheet of floating ice. But a new study published in the journal Polar Record suggests the ship’s entire structure was to blame, lacking the reinforcement needed to withstand ice compression. Interestingly, Shackleton might have known about this fatal weakness before setting sail.

“Even simple structural analysis shows that the ship was not designed for the compressive pack ice conditions that eventually sank it,” says study author Jukka Tuhkuri, a solid mechanics and ice researcher at Finland’s Aalto University, in a statement. “The danger of moving ice and compressive loads—and how to design a ship for such conditions—was well understood before the ship sailed south.”

Endurance set sail from England on August 8, 1914, with 28 men (including a stowaway) and 69 dogs on board. Led by Shackleton, the expedition aimed to cross Antarctica, beginning at the Weddell Sea and ending at the Ross Sea. The crew sighted the Antarctic continent in January 1915, but the ship soon became beset in pack ice. That October, the group abandoned Endurance and set up camp on a floating mass of ice, drifting with their ship. Then, on the evening of November 21, Shackleton shouted, “She’s going, boys!” The explorer and his men watched helplessly as Endurance sank

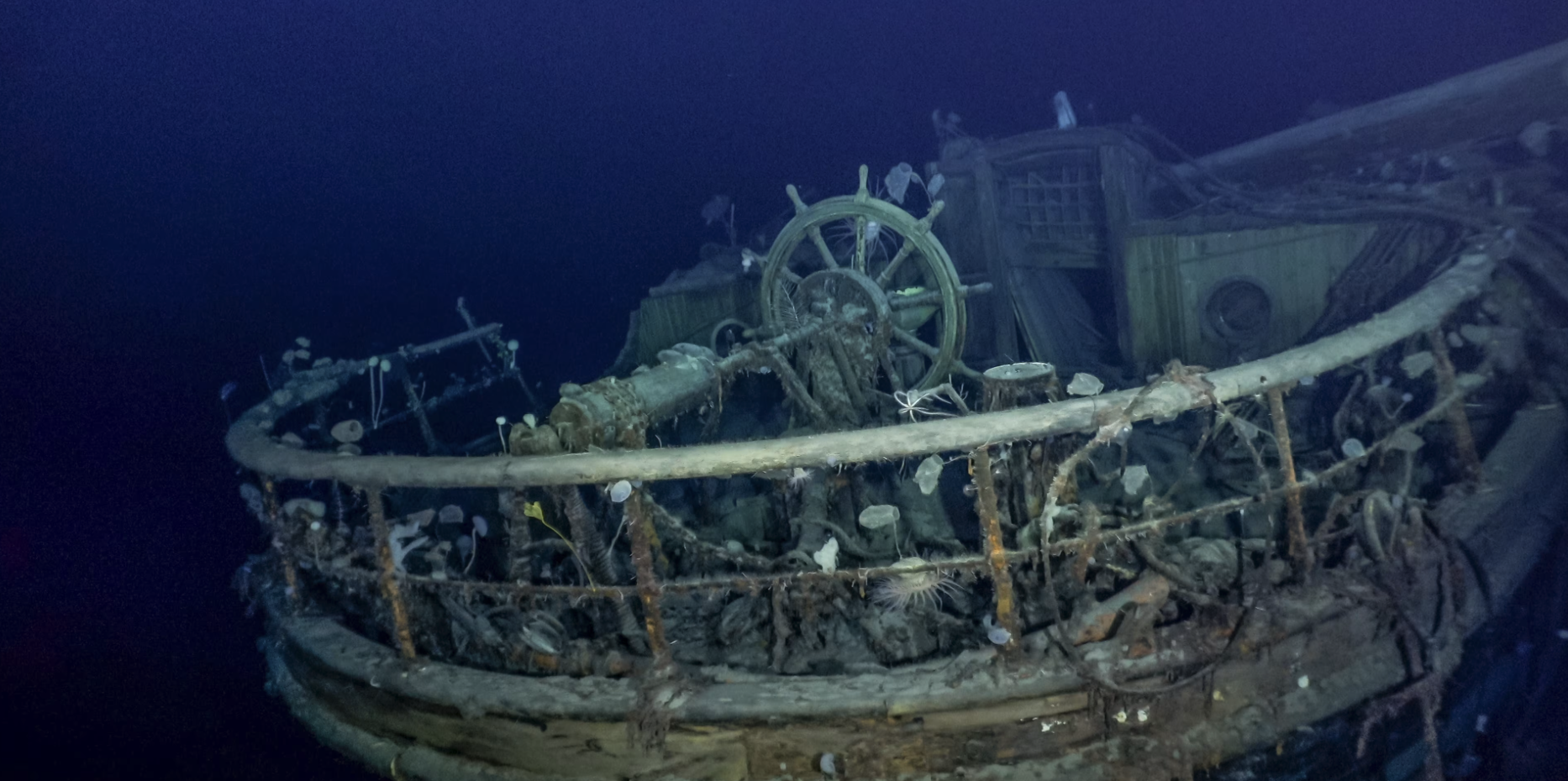

Tuhkuri was one of the scientists who worked on the Endurance22 expedition, which discovered the wreck of Shackleton’s ship in 2022. The find inspired Tuhkuri to research Endurance’s sinking. After examining archival images of the vessel, he recalls to the New York Times’ Sara Novak, he thought, “It’s not the ice, it’s the ship.”

As Tukhuri explains in the statement, “Endurance clearly had several structural deficiencies compared with other early Antarctic ships.” The ship’s deck beams and frames were weaker, and a too-long machine compartment weakened its hull, which in turn lacked strengthening diagonal beams.

The paper offers several examples of Endurance’s structural failings. In October 1915, crew member Reginald James wrote, “The pressure was mostly along the region of the engine room where there are no beams of any strength.” Around the same time, Endurance’s captain, Frank Worsley, described its engine room as “the weakest part of the ship.”

Tukhuri argues that Shackleton knew about Endurance’s shortcomings. Early in the expedition, he wrote to his wife from Buenos Aires, saying, “This ship is not as strong as the Nimrod constructionally. … I would exchange her for the old Nimrod any day now except for comfort.” (The Nimrod was a whaling ship Shackleton used during an earlier expedition, while Endurance was originally built to bring tourists to the Greenland Sea.)

Endurance was “designed to work at the edge of the pack ice but not to be frozen in,” Walt Ansel, a senior shipwright at Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut who was not involved in the new study, tells the Times.

“Shackleton’s aim was just to get to the continent and drop off supplies, so you might want a vessel that is more maneuverable for that,” Michael Bravo, a historian at the University of Cambridge who also wasn’t involved in the study, tells the Telegraph’s Sarah Knapton. “Maybe it wasn’t optimal for the sea ice, and with hindsight it could have been stronger, but it was intended for a different purpose than the polar expeditions that anticipated getting stuck in the ice.”

After Endurance sank, its crew endured another several months stranded in Antarctica. They went 497 days without standing on solid ground, only reaching the remote Elephant Island in April 1916. While most of his men stayed on Elephant Island, Shackleton and a few fellow sailors sailed out in search of help. They returned to retrieve those left behind on August 30. Remarkably, all 28 crew members survived the treacherous two-year expedition.

Could all of this suffering have been prevented if Shackleton chose a better ship for his Antarctic expedition? Was he aware of the risk he was taking? Tuhkuri resists placing blame. “We can speculate about financial pressures or time constraints, but the truth is we may never know why Shackleton made the choices that he made,” the researcher says in the statement. “At least now we have more concrete findings to flesh out the stories.”

Source: smithsonianmag.com. Sonja Andersen. Images: James Blake/Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National Geographic