On October 13, 1902, a steamship full of iron ore was towing a uniquely shaped barge across Lake Superior. The two ships encountered a powerful storm, which snapped the towline connecting them, leaving Barge 129 at the mercy of the winds.

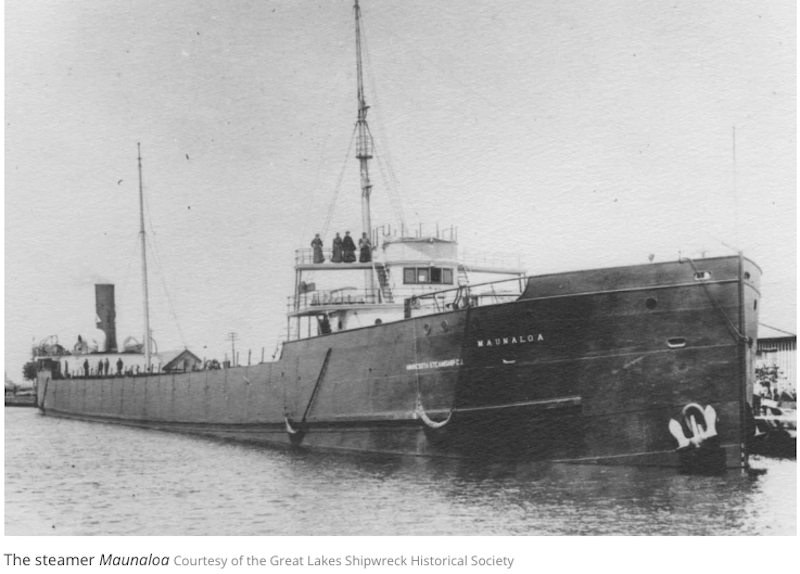

The crew aboard the steamer, called Maunaloa, turned their vessel around and tried to reconnect the towline, but the weather had other plans: The massive waves and strong winds slammed the ships together. The collision ripped a hole in Barge 129’s starboard side.

As Barge 129 began to take on water, the vessel’s quick-thinking captain, Josiah Bailey, gathered his crew and launched the lifeboat. Eventually, the men reached the safety of Maunaloa—but their ship sank some 650 feet below the surface. And that’s where Barge 129 has remained for the last 120 years.

As Barge 129 began to take on water, the vessel’s quick-thinking captain, Josiah Bailey, gathered his crew and launched the lifeboat. Eventually, the men reached the safety of Maunaloa—but their ship sank some 650 feet below the surface. And that’s where Barge 129 has remained for the last 120 years.

Now, researchers with the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS) say they’ve finally discovered the location of the doomed ship.

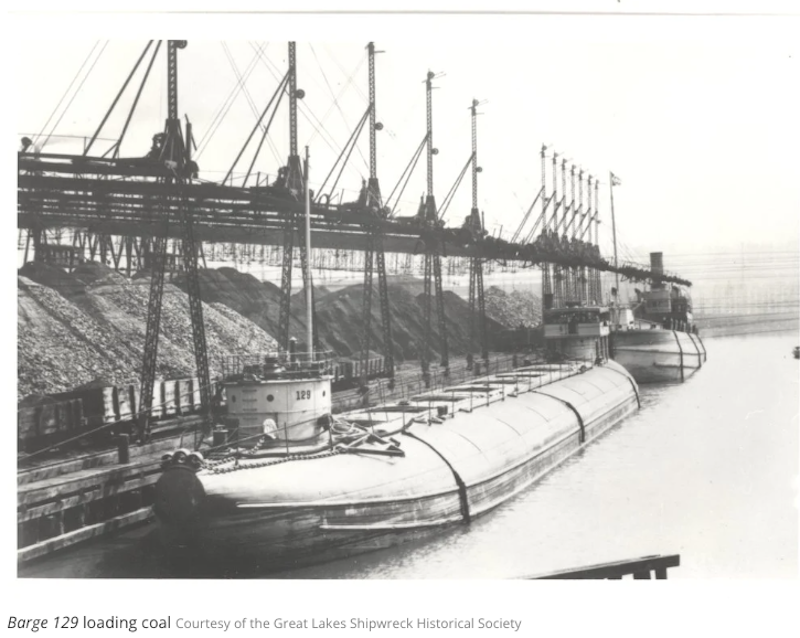

Barge 129 was somewhat unusual because of its design: It was one of only 44 so-called “whaleback” ships ever constructed. These vessels had curved sides and pointed bows with flat ends reminiscent of a pig’s snout. Barge 129 was the last undiscovered whaleback wreck in the Great Lakes, reports CNN’s Taylor Nicioli. Just one surviving whaleback, the S.S. Meteor, remains intact today. It’s maintained as an immersive museum in Superior, Wisconsin.

The historical society’s researchers first encountered the remains of Barge 129 in 2021 while using side-scan sonar, a detection and imaging technology that sends acoustical pulses to the lake floor. But the sonar images of the vessel weren’t clear and the researchers were skeptical as to whether they were actually looking at the historic 292-foot whaleback

This summer, they sent an underwater drone down to get a better look. Diving deep under the water roughly 35 miles off Vermilion Point, the drone confirmed their suspicions. “You could clearly see the distinctive bow with a part of the towline still in place—that was an incredible moment,” says Bruce Lynn, the historical society’s executive director, in a statement.

After 120 years at the bottom of the chilly Lake Superior, Barge 129 was in rough shape. From the video footage and photos, researchers could tell the vessel had mostly disintegrated, though four or five big pieces remained intact.

After 120 years at the bottom of the chilly Lake Superior, Barge 129 was in rough shape. From the video footage and photos, researchers could tell the vessel had mostly disintegrated, though four or five big pieces remained intact.

Researchers with the historical society, which also runs a museum on the southeastern shores of Lake Superior in Paradise, Michigan, regularly scour the Great Lakes for wrecks. Last year, they found the 172-foot Atlanta, a schooner barge that sank in May 1891.

The historical society has also been involved in efforts to preserve and protect the remains of the Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank on Lake Superior in November 1975 and lost all 29 members of its crew. That wreck is perhaps the best-known of all the Great Lake wrecks thanks to singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot, who wrote a haunting ballad about the tragedy, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” in 1976. The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum has the Edmund Fitzgerald’s 200-pound bronze bell in its collection at Whitefish Point, as well as an array of other shipwreck artifacts.

All told, there are an estimated 6,000 shipwrecks across all of the Great Lakes—Superior, Huron, Michigan, Erie and Ontario—which were popular shipping routes for coal and iron ore during and after the Industrial Revolution. More than 30,000 mariners have died as a result of wrecks on the lakes, per the historical society.

Though ships like Barge 129 aren’t well-known among the general public, their discoveries nonetheless give researchers an opportunity to share more about the legacy of shipping on the Great Lakes—and the high levels of risk mariners assumed while working in the industry.

Source: Sarah Kuta - Smithsonianmag.com