This Yacht Trafficked Enslaved Africans Long After the Slave Trade Was Abolished

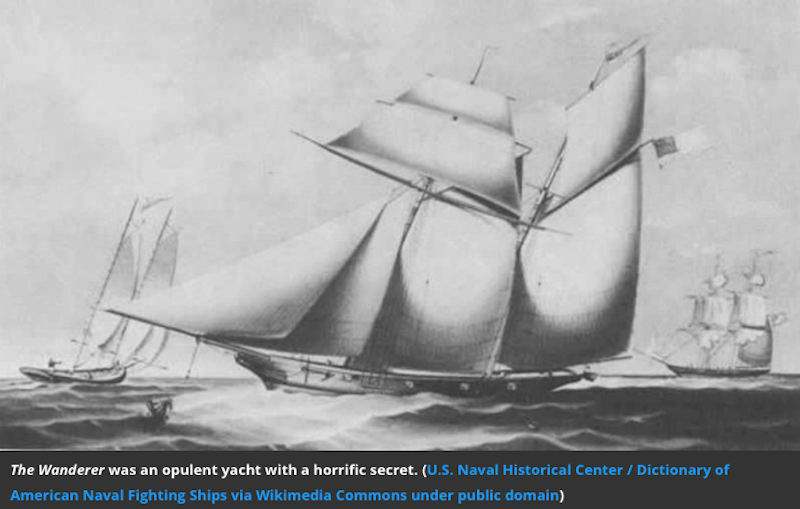

The 19th-century ship the Wanderer was an opulent pleasure yacht with a sinister underside: a hidden deck where hundreds of enslaved Africans were held captive and illegally trafficked into the United States. Now, almost 165 years after the Wanderer’s final voyage, the Finding Our Roots African American Museum in Houma, Louisiana, is telling the stories of the people who survived the transatlantic crossing and went on to live in the American South.

As Margie Scoby, president and curator of the museum, tells the Courier’s Kezia Setyawan, creating the museum’s newest exhibition—titled “Blood, Sweat and Tears”—was a fulfilling and deeply personal experience “Believe it or not, I’m excited because I found out it’s one of my families who was on board,” she says. “It can become overwhelming, but my ancestors drive me.”

Finding Our Roots unveiled the exhibition during a grand reopening held last month. Like many institutions across the country, the museum has been closed for the past year due to Covid-19 restrictions.

“This museum depicts so much and exposes the beauty we have regardless of the challenges we have faced,” Thibodaux City Councilwoman Constance Johnson, who attended the April 24 reopening, tells Setyawan for a separate Courier article. “Today is a day of love.”

Per the Associated Press (AP), “Blood, Sweat and Tears” features soil collections from plantations in the area, photographs from the last years of legal slavery and documents that can help visitors investigate their own family connections to the people enslaved on local plantations.

“This brings us the strongest and the best who pour themselves into culture and heritage and leave us a legacy that will tie each of us together,” Betsy Barnes, press secretary for Louisiana Lt. Governor Billy Nungesser, tells the Courier.

Though Congress prohibited the trafficking of enslaved people from outside the country in 1808, the underground slave trade continued until close to the start of the Civil War. The Wanderer was one of the last known illegal slave ships to enter the U.S. As Christopher Klein wrote for History.com in 2016, William Corrie and Charles Lamar—two prominent “fire-eaters,” or advocates for the reopening of the international slave trade—purchased the yacht in 1858 and retrofitted it to hold captives, installing a hidden deck and a 15,000-gallon freshwater tank.

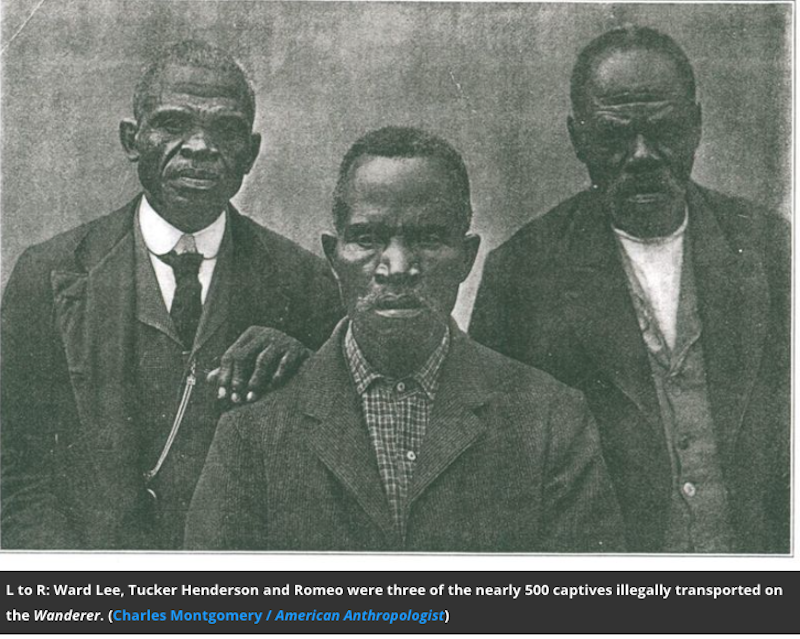

In July 1858, the ship left port while flying the pennant of the New York Yacht Club, where Corrie was a member. The crew sailed to the west coast of Africa, where they purchased almost 500 slaves, most of them teenage boys. Many of the enslaved people died on the six-week voyage, but around 400 made it to Jekyll Island, Georgia. They were then sold in slave markets across the South.

Given the impossibility of keeping the influx of captives from Africa into the slave markets quiet, Corrie, Lamar and others involved in the scheme were soon arrested and tried in federal court in Savannah. But the jury of white Southern men refused to convict them. (According to the Massachusetts Historical Society, one of the judges in the case was actually Lamar’s father-in-law.)

In May 1861, the federal government seized the Wanderer as an enemy vessel and used it in blockades of Confederate ports. The ship eventually sank off the Cuban coast in 1871

Writing for the Magazine of Jekyll Island in 2018, Rosalind Bentley reported on the life of a survivor of the Wanderer: Cilucängy, later known as Ward Lee. Just five years after his arrival in the U.S., Lee was freed, but he remained stranded in a foreign country. Years later, he penned a public letter seeking help returning to Africa. The missive read, “I am bound for my old home if God be with me.” But Lee was never able to return home. His great-great grandson, Michael Higgins, told Jekyll Island that Lee instead became a skilled artisan. Higgins recalled his grandmother telling stories about her grandfather while holding a walking cane he had carved. “She said he always talked about how we had to keep the family together,” Higgins explained.

The last known slave ship to arrive in the U.S., the Clotilda, has also been at the center of recent efforts to reconnect families with their histories. In 2019, researchers discovered the remains of the ship along the Mobile River, as Allison Keyes reported for Smithsonian magazine at the time. The Alabama community of Africatown, founded by some of the descendants of people trafficked on the Clotilda, worked with historians and researchers on the project.

“One of the things that’s so powerful about this is by showing that the slave trade went later than most people think, it talks about how central slavery was to America’s economic growth and also to America’s identity,” Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch, then the director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, told Smithsonian. “For me, this is a positive because it puts a human face on one of the most important aspects of African American and American history. The fact that you have those descendants in that town who can tell stories and share memories—suddenly it is real.”

Source: smithsonianmag.com